Previously, we explored the early days of the Renaissance. Today, let’s delve deeper into its background.

In the 14th century, Europeans were eager to move on from the dark Middle Ages. This era had been marked by devastating events like the plague, which wiped out 60% of the population in Europe. Widespread poverty, numerous wars like the Hundred Years War, and a lack of law and order added to the hardships. Disputes within the Christian church, combined with its conservative views and strict doctrines, led many people to question the role of the Catholic Church and God in their lives.

Previously, we examined the Trecento period, often considered the dawn of the Renaissance. The Trecento, marking the late Middle Ages in 14th-century Italy, was a time of dissatisfaction with daily life. The idea of living a happy life and loving others was not widely accepted in Christianity, as there was intense pressure to keep God at the center of people’s lives: A person should devote their life to God, love Him wholeheartedly. One was expected to embrace suffering rather than happiness to attain eternal salvation and secure a place in heaven.

People began reflecting on their way of life, comparing it to the classical Greek and Roman cultures, which seemed to have had greater freedom and joy, free and without strict rules and dogma. Unlike the medieval period, Greek and Roman scholars could openly explore fields like mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy—areas that stagnated during the Middle Ages. The Greeks and Romans displayed a deep curiosity about the universe, Earth, and humanity, while people in the Middle Ages appeared more passive in comparison.

However, as this dark period ended, a new and hopeful era began to emerge.

Inspired by the lifestyle and values of classical Greeks, Petrarch’s writings ignited a renewed fascination with ancient Greek and Roman culture. During the Trecento, Petrarch was starting to revive and rejuvenate these classical works.

Petrarch (1304-1374)

Petrarch’s Canzoniere, a collection of 366 poems dedicated to Laura, is considered his masterpiece. Petrarch began writing these sonnets shortly after he allegedly encountered Laura de Noves in Avignon in 1327. He continued to work on and refine the collection throughout his life up until his death in 1374. It explores unrequited, desperate, eternal, and tragic love through his idealized beloved, Laura. Petrarch’s perfection of the sonnet form (14-lines octave and a sestet: ABBA ABBA – CDC DCD) and his influential treatment of courtly love made him one of the most important poets in the history of world literature. His work inspired generations of poets, writers, and artists.

- Humanism: Petrarch is often called the “Father of Humanism” due to his emphasis on studying classical authors, and his belief in humanity’s potential for achievement.

- Shift from religion: Petrarch’s works moved away from the strictly theological focus of medieval literature, paving the way for a more human-centered approach to knowledge and emphasizing individual emotions.

- Visual arts: His descriptions of Laura provided artists with vivid sources for interpretation.

- cultural shifts: The popularity of Petrarch and Laura’s love story, particularly after the invention of the printing press, swept the Renaissance reading public.

- critical thinking: Petrarch’s work helped inspire the development of humanism, which later led to the framework for scientific research and logical analysis

Sonnet 3 from Petrarch’s Canzoniere “Era il giorno ch’al sol si scoloraro”.

This sonnet is one of the best-known, because in it Petrarch situates the very beginning of his love for Laura:

It was the day when the sun grew dark,

out of pity for its Maker’s suffering,

when I was captured, and did not defend myself,

for your beautiful eyes, my lady, bound me.It seemed no time then to guard against

Love’s blows: so I went on unarmed,

without suspicion — and so my troubles

began amidst the world’s great sorrow.Love found me completely disarmed,

and opened the way through my eyes to my heart,

which is now the gate and passage of tears.And so, it seems to me, it was no honor

to wound me with his arrow in that state,

while you, armed, did not even show the bow.

In this Sonnet we can see the all of the themes: unrequited love, suffering and devotion, but also Christianity and Greek Mythology. It intertwines sacred time (Good Friday) with personal time (the start of his love for Laura), showing how Petrarch fuses his spiritual, emotional, and poetic worlds.

- It was the day when the sun grew dark,

Reference to Good Friday, when the sun was said to darken at Christ’s death (Matthew 27:45). - out of pity for its Maker’s suffering,

Nature itself mourned the crucifixion - when I was captured, and did not defend myself,

On that very day, Petrarch “fell in love,” taken prisoner by Laura’s beauty. He did not “guard” himself. - for your beautiful eyes, my lady, bound me.

Her eyes are chains — classic medieval love imagery: the lover enslaved. - It seemed no time then to guard against

Because it was Good Friday, a sacred day, his heart was unguarded. - Love’s blows: so I went on unarmed,

He wasn’t thinking of protecting himself from Cupid’s arrows. - without suspicion — and so my troubles

- began amidst the world’s great sorrow.

While the whole world mourned Christ, his personal grief began: the suffering of love. - Love found me completely disarmed,

Cupid came upon him defenseless. - and opened the way through my eyes to my heart,

Eyes are the traditional gateway to the soul in courtly love poetry. - which is now the gate and passage of tears.

His heart is a place of weeping, love’s gate open forever. - And so, it seems to me, it was no honor

A protest: Cupid acted without chivalry. - to wound me with his arrow in that state,

To shoot him when he was unarmed, mourning, vulnerable. - while you, armed, did not even show the bow.

Cupid never even bothered with Laura; she is strong, armed, untouched.

Humanism

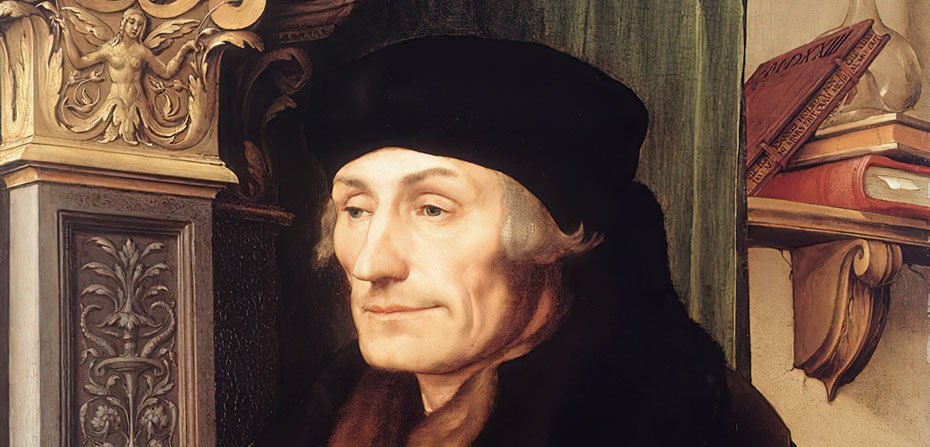

During the Renaissance, the study of ancient Greek and Roman cultures evolved into a movement and philosophy called “humanism.” The Dutch Catholic priest and scholar Erasmus (1467–1536), was one of the most prominent Christian Humanists of the Northern Renaissance. He embraced humanism while maintaining his Christian beliefs, exploring ways of life and lifestyles by drawing inspiration from classical works.

Humanism represented a shift from the medieval emphasis on religion to a focus on human potential and achievements. Erasmus utilized humanist approaches to reform Christian thought and tackle church corruption. Renaissance Humanism highlighted individual potential and promoted education in the “humanities,” including grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy.

- Emphasis on human potential: Humanists believed that humans were rational and self-aware beings capable of personal improvement.

- Study of classics: The movement was founded on the belief that a return to ancient Greek and Roman texts was the best way to develop moral, rational, and eloquent citizens.

- Rejection of scholasticism: Humanists turned away from the complex, often abstract, and dogmatic university teachings of the Middle Ages, which they found unhelpful for living a good, practical, and moral life.

- Focus on this life: While not rejecting Christian divinity, Renaissance Humanists concentrated on human interests and values in the natural world rather than solely on preparing for the afterlife.

This movement encouraged people to seek happiness and fulfillment. Simultaneously, the dominance of Christian faith began to wane. From this point forward, humans, rather than God, were regarded as the center of the universe. Humanity was perceived as inherently good rather than sinful and was celebrated for its intelligence and curiosity.

Curiosity

Humanism emphasized placing humans at the heart of exploration, embracing reason, creativity, curiosity, and the pursuit of knowledge across various fields. It inspired artists, scientists, and thinkers to study the natural world, delve into understanding the world both on Earth and beyond, explore the human form, and appreciate the achievements of antiquity, not just to mimic them but to build upon them.

This newfound curiosity drove Europeans to explore distant lands, invent, and create stunning works of art. Starting with the Renaissance, improvements in navigation technology allowed Europeans to journey across the globe, leading to overseas trade and conquests, like Columbus’s discovery of the Americas in 1492.

Few figures embodied these ideals as fully as Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).

Often hailed as the ultimate “Renaissance man,” Leonardo distinguished himself in painting, anatomy, engineering, and invention. His artworks, including The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa, demonstrated revolutionary mastery of perspective, light, and human expression, transforming the possibilities of visual representation. His dissections of the human body advanced anatomical knowledge, allowing him to portray muscles, movement, and proportion with remarkable accuracy.

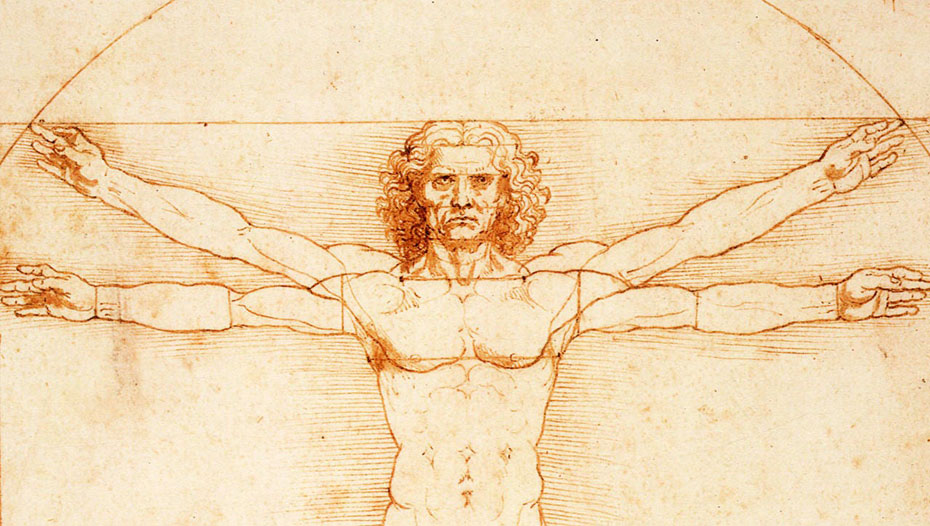

One of Leonardo’s most famous drawings, the Vitruvian Man, illustrates his fusion of art and science. Inspired by the writings of the Roman architect Vitruvius, the drawing depicts a male figure inscribed within a circle and square, symbolizing the harmony between the proportions of the human body and the geometry of the cosmos. It is both a scientific study of anatomy and a philosophical statement about humanity’s place within nature—a perfect embodiment of Renaissance Humanism.

Beyond his art, Leonardo’s notebooks reveal an intellect centuries ahead of its time. He designed machines resembling modern helicopters, tanks, and bicycles, studied optics and hydraulics, and sketched architectural innovations. Although many of these designs were not realized during his lifetime, they demonstrate his ability to merge observation with imagination, uniting practical engineering with visionary speculation.

Leonardo’s accomplishments underscore the broader values of the Renaissance: the integration of knowledge across fields, the pursuit of truth through both empirical study and artistic expression, and the belief in the vast potential of human creativity.

His legacy lies not only in his masterpieces but also in his embodiment of the Renaissance ideal—A person driven by curiosity and intellect, striving to explore and express the deep connections between art, science, and the human experience.